Trial

Arraignment

After their capture in Arkansas, the

brothers were held in the Buchanan County jail in St. Joseph until

the arraignment. At St. Joseph, the Taylors were model prisoners,

attended religious services in the jail, and submitted to newspaper

interviews. But Bill did all the talking and when questions were

directed to George, Bill interrupted to give the answer. They

hired lawyers, with the aid of their father, who came to St. Joseph

and planned their defense. Bill boastfully declared that they

would stand trial in Linneus when their case came up the first

Monday in December. They had little fear of their old

associates in Linn County, Bill declared, and they would be willing

to go to trial without guard. (There had been many threats on

their lives.)

On December 14, 1894, the Taylor brothers left St. Joseph for

Linneus with an armed guard consisting of the Linn County sheriff

and six deputies. A special car took them to Laclede and then

the branch line transported them to Linneus where sixteen more

deputies lined up at the station to keep back the throng.

After a noon meal in the court house, the Taylors' attorney,

D.M. Wilson of Milan, entered a plea of not guilty for the

defendants. He then immediately asked for a change of venue.

Judge William W. Rucker sent the case to Carroll County,

south and west of Linn county. Since this was in his circuit,

he would be the presiding judge. After the arraignment, they

were confined in the Carroll County jail.

First Trial

The trial began March 18, 1895, in Carrollton,

Mo. Carloads of people came in on the railroads from Sullivan

County and surrounding areas. The Taylor brothers arrived,

neat and well-groomed, and apparently not nervous. They

maintained they were innocent and seemed confident they would be

cleared.

The jury consisted of twelve men from the

Carrollton area, all farmers except one merchant: Davie

Jamison, Barnett Hudson, W.R. Brammer, Benjamin Glover, George

Fleming, Adolph Auer, Frank Yehle, Elijah Baker, J.T. Noland, James

Creek, J.A. Ross, and Granville Jenkins.

The prosecuting attorney was T.M. Breshnehen, and

the defense attorney was Colonel John Hale. The defense

waived the right to make an opening statement. The

prosecution's opening statement centered on the fact that George

and William were seen fleeing the Browning area, two hours before

the report of the discovery of the bodies had made its way to

Browning. He also pointed out that blood had been found in a

wagon belonging to their father, James Taylor, and that Taylor and

a hired hand had attempted to burn out the blood marks. Also,

William had been heard to say that they were going to have to get

rid of Gus Meeks before he could testify against them in a trial

regarding cattle rustling.

Several witnesses from around Jenkins Hill testified to

having seen the bodies. They testified to the gory condition

of the bodies and about the track around the straw stack.

Mrs. Kitty Edens came to the stand an testified to having

heard five shots just after midnight, the morning of May 11, 1894.

She lived within 600 yards of Jenkins Cemetery. Harry Wilson

testified to examining the ground near the Jenkins Cemetery; L.C.

Lantz testified to seeing sign of a disturbance at Jenkins Hill and

that he found a revolver, which was later given to one Isaac

Gwinn.

The mother of Gus Meeks, Mrs. Martha Meeks, 64,

lived in the same house with her son. She told about how the

Taylor brothers often visited her son, and how they asked to see

him after the returned from the penitentiary, and how she overheard

the conversation in which the Taylor brothers agreed to give Gus

$1,000 to leave the area. On the Tuesday before May 10,

her son Gus had gone to Cora and reported that he had made an

arrangement with George and William Taylor who would give him eight

hundred dollars and a trunk to leave the country and not testify

against the Taylors at a trial to be held in Sullivan county.

Mrs. Meeks said she was always afraid the Taylor

brothers would kill her son. She testified Gus received a

letter May 10, which had the heading of the People's Exchange Bank

of Milan. It read, "Be ready at 10:00. Everything is

right." It had three stars for a signature. She tried

to persuade her son not to go, but that night George Taylor came in

and helped Gus carry out the household goods. Gus told his

mother that William was outside, but Mrs. Meeks said she did not

see him.

Several people testified to having seen the

Taylor brothers out in the wagon about 10 o'clock the night of the

murder. A man named Dillinger testified that Bill Taylor had

told him he would kill Gus Meeks.

Mrs. John Carter told about how Nellie had

appeared on her doorstep and relayed everything Nellie had told

her. Jimmy Carter told of his experiences when he talked to

Nellie and found the bodies. Several witnesses testified to

seeing blood stains in the Taylors' wagon, and several said they

saw George Taylor riding home at a fast rate early in the morning

of May 11.

Jerry South, member of the Arkansas legislature

and captor of the Taylor brothers, took the stand for the state.

He had received $1,500 from Linn County for capturing the

pair, and if they were convicted, he would receive $500 from the

state. The defense insinuated that this was the reason South

was testifying for the state.

Most of the witnesses for the defense were

relatives of the defendants. Some cousins and the

mother of George and Bill testified they had seen no blood in the

wagon, only old, dried, red paint. Mrs. George Taylor

testified that her husband had slept in her bed all night May 10.

Mrs. William Taylor testified her husband had returned home

at 10 p.m. May 10 and had slept until 5 a.m. On cross

examination she was asked if she had told Rev. P.M. Best that her

husband was gone all night the night of the murder. She

denied saying any such thing.

Then Bill Taylor himself took the stand. He

gave some general information about himself and his education.

Then he told what he did the night of the murder. He

said George went home with him at 4 p.m. on the 10th. They ate

supper together, and then George went home and Bill went back to

the bank, where he worked until 10 p.m. He said he went home

then, and slept until 5 o'clock the morning of the 11th. He

said George came to the bank just after 8 a.m. and told him that

Gus Meeks was dead and the body was on his place.

George wanted to get an officer and take him down

to investigate, but Bill said he thought they were being framed

because it was general knowledge that Meeks was going to testify

against them. So Bill recommended they simply wait and see

what developed. George Taylor took the stand. He more

or less matched Bill's testimony.

The case was given to the jury April 9, 1895, but

they failed to reach a verdict. There was talk on the streets

of Carrollton of jury bribery. One man, who was on the panel,

but not on the jury, declared that he had been offered $750 if he

got on the jury and declared that another man, who was on the jury,

had a similar offer. The evidence against the Taylors seemed

overwhelming. The trial ended and the jury retired.

They stayed in retirement for two days. Rumors flew

around that they stood 11 to 1 for conviction. In Missouri,

juries in criminal cases must reach a unanimous agreement.

Finally, ,the jury reported to the judge that they could not

agree. They stood 7 to 5 for conviction of their final

ballot. Outraged, the judge dismissed the jury,

declared the case to be a mistrial, and returned the prisoners to

jail to await a new trial.

Second Trial

The second trial of the Taylor brothers was begun in

July, 1895. The state's attorneys seemingly believed that a

first-degree murder charge could be made to stick only in the case

of the killing of Gus Meeks, since a first-degree murder is one

that requires premeditation. The evidence that thee was

premeditation in the murder of Mrs. Meeks and the two babies might

have been a bit shaky. The state wanted to convict the

Taylors of a crime for which they could be hanged. There were

filed in Linn County three other indictments covering the murder of

the mother and two children and one other charge of assault, but

the case against the Taylors for the killing of Gus was the one

which the state's attorneys considered the best to try for a

first-degree conviction.

More care was taken in the selection of the

second jury. G.W. Craig, a cousin of Defense Attorney Ralph

Lozier was the foreman of the jury, but the state's attorneys did

not contest this. The following made up the second jury:

E.J. Calloway; F.B. Creason; T.N. Houghton; John M.

Edge; B.C. Dulaney; J.S. Helm; G.F. Morris; R.G. Evans; G.W. Shank;

George Freeman; W.H. Vaughn; and G.W. Craig.

At the first trial the defendants had made no

statement as to what their case would be. But this time,

Colonel Hale gave his attention to explaining why the defendants

fled--he would produce testimony for the defense to show, he said,

that they fled because their lives were endangered by mob violence

(the bodies had been found on their property). He

characterized Gus Meeks as belonging to the criminal class, and

Colonel Hale tried to picture the Taylors as protecting themselves

against a conspiracy, a dangerous feuding group.

For the prosecution, Walter Gooch testified to

seeing George Taylor leave his home south of Jenkins Hill and

tended to implicate Albert Taylor in the crime. He told

of overhearing a conversation in which George told Albert (a

brother) on the afternoon before the murder to be sure to do what

he told him to. This, however, was as near as anyone came to

making Albert an accessory to the crime. There was no

follow-up.

Additionally, Mrs. Meeks testified that she

begged Gus not to go that evening her testimony was: "He stooped

down and kissed me; I told him it was a trap; he says, 'Mother if

you don't hear from me by Thursday'"--she was stopped by an

objection registered by the defense. Mrs. Meeks' testimony

was extremely important because if not contravened it would destroy

any alibi which the Taylors' lawyers might attempt to establish.

Mrs. Meeks' testimony evidently did stand and was a major

point which brought about the conviction of the Taylors.

The state next turned its attention to threats

which Bill Taylor had made. M.S. Burdett, blacksmith, whose

place of business adjoined the People's Exchange Bank of Leonard

and Taylor on the east, testified: "I asked him what about Gus

Meeks coming back, and he said he knew what the damned...came back

for, and he would get what he came for."

L.B. Phillips, a farmer living four miles west of

Browning, stated that he had had a conference with Mr. Taylor in

reference to Gus Meeks and his testifying against him, ,"I think

this was on Monday before the murder, about May 6, 1894; that

evening William P. Taylor went out with me pretty near to my house;

I said to him, 'Bill, what are you going to do with Meeks; he has

come back.' He kinder smiled and said, 'We will have to get him out

of the way.' I asked him how he was going to get him out of the

way; he said he did not know how he would get him out of the way,

but he would get him out of the way if he had to kill him to get

him out of the way." Phillips said that he had reported this

conversation to his friend George Novel the evening before the

murder committed.

Other testimony revealed that George had been out

harrowing his newly planted corn field (early that morning) around

the haystack, ostensibly to cover up the wagon tracks that had been

made when the wagon carrying the bodies had been driven across the

field. (Other testimony showed that due to the heavy rains

two days before, no one would have logically been harrowing.)

Jerry South, who was responsible for the arrest

of the Taylors in Arkansas, also testified. A legislator,

South had seen the Taylors during a dinner at Hays Inn in Buffalo

City. They were introduced as William Price and George

Edwards, who claimed to be timber prospectors. Later, he

suspected that they might be the Taylors, sought out photos of

them, and then a couple of days later, on passing through Buffalo

City again, he talked to the mysterious strangers who told him they

AHD been making a boat in order to continue their explorations.

South went to the store of E.L. Hays and asked for a

double-barreled shotgun. He did not get one, but he did get

one from a local resident, Mr. Tonstil. He then yelled to the

Taylors, about 75 yards away, calling, "Halt. You are under

arrest." They turned around and Bill Taylor reached for a front

pocket. But South warned him not to pull a weapon. They first

started to come to South, who told them to stop. He asked

them if they had weapons. Bill said he had a pistol; George

said he had none. South called Captain Albert Cravens, pilot

of the small river steamer on White River. Cravens took

Bill's pistol. Two other pistols were found at the home that

the men had been occupying.

South took the men to a small building where he

guarded them overnight and with them started for Little Rock the

next day. The Taylors first threatened South with a suit for

false arrest, ,but after he showed them the pictures he had, they

admitted their identity and stated that they were tired of hiding

and were waiting to be taken back. After his meetings in

Little Rock, South delivered them St. Louis and into the hands of

Sheriff Barton of Linn County. On the train, Bill told

Mr. South that he and George had taken the Meeks family as far as

Stone's Corner, near Browning, that they had given Gus a thousand

dollars and dropped off the wagon. At this distance in time,

it looks as if the Taylor's defense might have been better if they

had stuck to this story instead of denying that they had ever left

home.

Mrs. Dave Gibson, mother of George Taylor's wife,

had testified that she had spent the night at the George Taylor

home, helping tend to their baby. She testified that George

came home early in the evening, went to bed, and that she saw him

there several times during the evening and early night.

During later testimony, Garnett Atkins said he had know Mrs.

Gibson for more than twenty years and that he had had a

conversation with her in which she said that she did not know

whether George was implicated in the murder or not, that she had

"set up" until ten o'clock waiting for him, and that she had then

gone to bed; ;she said that she was awake before he came in and it

was after four o'clock, but not yet five; she told Atkins that she

let George in. This conversation was held at the George

Taylor home May 21, 1894.

Atkins, who was in a livery business, stated that Mr. and Mrs.

Gibson and Orville Shelby were present when Mrs. Gibson made the

statements to him. Several United States marshals had gone

with Atkins to the Taylor home t trying to learn where the Taylors

had gone, but only Mr. Shelby heard Mrs. Gibson's statement.

Mrs. George Taylor was recalled and denied that her mother,

Mrs. Gibson, had ever made the statement concerning the time of

George's return on the night of May 10-11. She felt sure that

Mrs. Gibson had made no statement to Atkins at all.

George Taylor's Testimony

George stated that he had gone home about nine

o'clock, his father's team hitched to his father's wagon. He

told of rising early on the morning of the eleventh, his going to

the cornfield and being engaged in harrowing the cornfield and

being engaged in harrowing the corn--when the small boy (Carter

boy) came to him with the story of the little girl who said that

her sisters were in the straw stack. He went to the straw, so

he declared, and dug around in it till he uncovered the face of Gus

Meeks. He then decided to ride to Browning for help, which he

did. He thought he ought to get an officer. But on

consultation with his brother, they decided it would be better to

go away. They were afraid of mob violence feeling that they

would be accused of the murder when people saw how they were

benefited by Meeks' being out of the way. (The Carter boy

testified that after he told George the news about the bodies, he

unhitched a team horse from a wagon and went directly to Browning,

not to the haystack.)

William P. Taylor Testimony

William testified to his everyday activities on

the day of the crime. He also told of his meeting Gus Meeks

at Cora. His story was the Gus was leaving to avoid being

taken to Ohio for a crime that he had committed there, that he had

$500 coming to him on an insurance policy which he wanted Taylor to

collect for him. He had agreed, he said, to give Meeks

$50. Taylor admitted that he had written the note to Gus

Meeks at Milan on May 10, which read: "Be ready at 10

o'clock; everything is right. XXX" Taylor did not explain,

nor was he asked to, that if neither he nor George went to Milan,

what meaning the note had. Bill told of George's coming in on

the morning of the eleventh and of their decision to get out of

sight.

The court adjourned at two o'clock on July 31 with

the conclusion of evidence. Within an hour and a half, they

returned a guilty verdict. The courtroom broke into pandemonium.

It was two hours before the prisoners could be transported to

the jail. The defense made a list of reasons why they would like a

new trial and submitted those to the judge at 10 p.m that evening.

He rejected those, and told them they would have to appeal to

a higher court. The judge sentenced the Taylors to hang.

There was an appeal to the Supreme Court of Missouri, and on

March 3, 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the verdict and set April

30, 1896, as the execution date. Judge Sherwood wrote 30 points to

support the guilty verdict, #1 of which was that they had made

threats to commit the crime; they had motive and the Meeks were

last seen alive in the presence of the Taylors. As Judge

Sherwood summed it up: "More cogent evidence of guilt

is rarely presented in a criminal cause.".

April 11, 1896, George and Bill Taylor broke

jail. Bill was recaptured, but his brother was never found.

George Taylor was reportedly seen from time to time, but he

was never captured. Several men on the deathbeds confessed to

being George Taylor.

Attempted Escape

After the Supreme Court verdict, the Taylors

were brought before Judge Rucker at Carrollton and heard the

sentence which commanded Sheriff George E. Stanley of Carroll

County to hang them on Thursday, April 30, 1896. Although

confined to prison walls in the Carroll County jail, the Taylors

were evidently able to communicate with friends and relatives and

former members of their "gang." There were confined

with a third man who had also been charged with murder, one Lee

Cunningham. The three of them planned to escape. They

had considerable freedom around the jail at times and they noted

the things which they thought might make escape possible.

The jail had a roof of sheet tin, which would be

easy to penetrate if they could get to it. Then they would

have to find some means of descent from the roof to the ground./

From the roof, there would be a drop of approximately 40 feet

which must somehow be negotiated. They noted that the sheriff

had a 50-foot length of hose which he used about the jail in

keeping it and the jail yard clean. The Taylors

and Cunningham were allowed the freedom of the jail under strict

surveillance.

About 8:30 on the evening of Saturday,

April 11, 1896, the jailer ordered the prisoners in and

locked the door after all had gone inside. He locked the

Taylors and Cunningham in a cell. But the Taylors had

substituted a bar which they had fashioned of soap for the iron bar

which locked them in. It was removed quickly and the three

men climbed atop the cells, thus being within a few feet of the

roof. They cut a hole in the attic and then through the tin

sheeting in just a few minutes. They took with them the

50-foot hose which they tied to a small pipe and then threw it over

the side.

Lou Shelton, Jail guard, who was just outside the

jail heard a commotion, saw Cunningham, and ordered him to put his

hands up. Bill Taylor was halfway down the hose. He

stopped and yelled to George, who was still on the roof, "Come on

down, George. We're caught." But George had an alternate

plan. On the opposite side of the jail was a smokestack

beside the roof and George ran over to this, swung out over the

roof's edge, and climbed down the stack. He reached the

ground and ran rapidly to the street. Waiting for him there was a

two-seated rig. Two men were in the front seat, and

when George climbed into the back seat, they drove off rapidly.

(Some accounts have him escaping entirely on foot.)

The sheriff had to take his two prisoners in and

lock them up before he could look for George. He had to climb

to the roof before he knew that George was gone. He then gave

the alarm, but George was by that time miles away. He had

perhaps a fifteen-minute start.

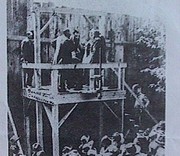

Execution

April 30, 1896, William Taylor was hanged in

Carrollton. Before his death he left this written

statement:

"To the public: I have only this additional statement to make. I ought not to suffer as I am compelled to do. Prejudice and perjury convicted me. By this conviction, my wife is left a lonely widow, my babies are made orphans in a cruel world, my brothers mourn and friends weep. You hasten my gray-haired mother and father to the grave. The mobs and that element have haunted me to the grave. I had hoped to live at least till the good people realize the injustice done me, but it cannot be so. I feel prepared to meet my God and now wing my way to the great unknown, ,where I believe everyone is properly judged. I hope my friends will meet me all in heaven. I believe I am going there. Goodbye all." W.P. Taylor

Launch the media gallery 1 player

Launch the media gallery 1 player